Tax Day 2017 has passed for individual taxpayers, but America’s tax bill is still due, and it’s a big one.

Taxpayers won’t pay off this year’s local, state, and federal tax burden totaling $5.1 trillion until April 23, or as the Tax Foundation calls it, Tax Freedom Day. That day, calculated annually, represents how long Americans work to pay local, state, and federal taxes for the year.

By the Numbers

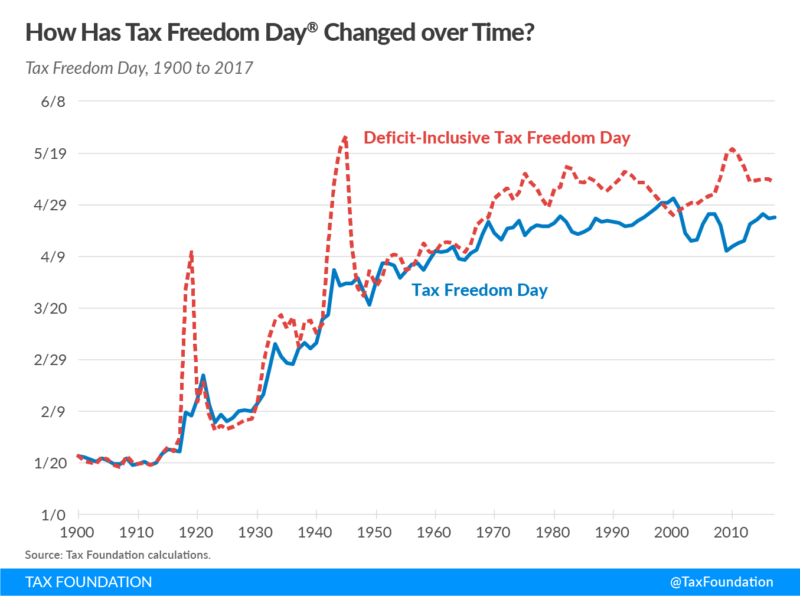

In 2017, it will take 113 days for taxpayers to pay the country’s tax burden, which includes $1.5 trillion in local and state taxes and $3.5 trillion in federal taxes, equaling 31 percent of America’s income. But that’s not all. If you include federal borrowing, which represents future taxes the government must collect to pay the bills, Tax Freedom Day would occur 14 days later this year on May 7.

To put this year’s total tax burden into perspective, the latest date for Deficit-Inclusive Tax Freedom Day took place during World War II almost three weeks later than this year’s date, occurring on May 25, 1945.

How Expensive is Government?

Americans will collectively pay close to $1 trillion more dollars for taxes than will be spent on essentials like food, clothing, and housing combined.

The federal deficit is expected to shrink by $45 billion to $612 billion in calendar year 2017, but the track record over the past few decades is not comforting. The cost of the federal government has surpassed its tax revenues since 2002, racking up budget deficits exceeding $1 trillion annually from 2009 to 2012.

According to the Tax Foundation’s data, Tax Freedom Day has changed dramatically over the past century. Notice how the date of Tax Freedom Day correlates with significant expansions of government since 1900, especially when considering the deficit-inclusive figures:

Focusing on Deficit-Inclusive Tax Freedom Day, economic liberty in America shifted abruptly in favor of the government while Woodrow Wilson was president. Wilson ushered in the Revenue Act of 1913 which re-imposed the federal income tax after the ratification of the 16th Amendment, followed soon after by the creation of the Federal Reserve in late 1913, and both led the way for deficit financing that enabled U.S. entry into World War I. After a subsequent reduction in federal tax burdens in the 1920s, the trend began to worsen considerably and hastened in the 1930s. American taxpayers then saw a substantial spike in government spending, deficits, and state power during Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s presidency and World War II.

Taxpayers saw a dramatic improvement in their financial freedom following World War II when overall tax burdens decreased in the 1950s, similar to the trend in the 1920s in the aftermath of World War I. But this new norm in the 1950s meant an additional two months of work to pay the government’s tax burden when compared to just a few decades prior. The overall trend, unfortunately, has been in the direction of Tax Freedom Day occurring later over the past sixty years, and considerably later compared to the trend of the past century, meaning less freedom from onerous taxation for Americans.

Tax Freedom in the States

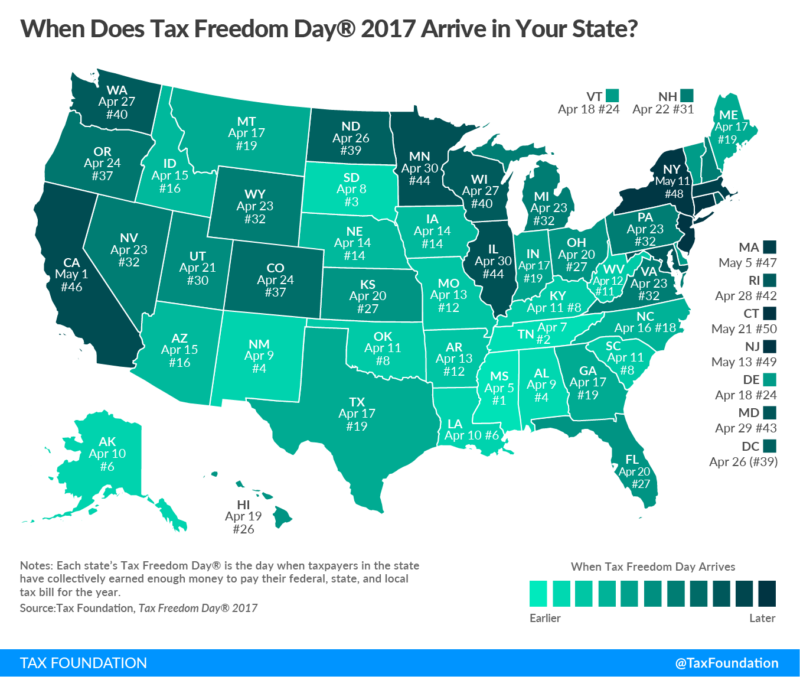

Tax burdens vary considerably state by state due to different tax policies and the progressive federal tax system. Each state has its own Tax Freedom Day which factors in local, state, and federal tax burdens for the taxpayers in their respective states.

States like Connecticut (May 21, #50), New Jersey (May 13, #49), and New York (May 11, #48) have higher taxes and residents earning higher incomes, so they celebrate Tax Freedom Day later than states like Mississippi (April 5, #1), Tennessee (April 7, #2), and South Dakota (April 8, #3), which bear the lowest tax burdens in 2017.

Taxes Are Revolting, Why Aren’t You?

The introduction of the Wilson era federal income tax and the Federal Reserve allowed for expansive government power and deficit financing. This also shifted the primary means of funding the government to income taxes and away from tariffs, as had been the practice. The federal government claims a right to your earnings and livelihood, essentially offering the ultimatum: your money or your life. Sheldon Richman wrote a book by that very title and argues that the income tax must be abolished altogether.

Reasonable people from various political viewpoints can disagree about how our tax dollars are spent or whether our earnings should be confiscated whatsoever, but Tax Freedom Day helps to put Americans’ overall tax burden into perspective. Furthermore, it highlights the paramount principle regarding the rights of individuals and government power:

If Americans are forced to work nearly one-third of the year just to pay taxes to the government, then how free are we?

View as PDF

On the 100th Anniversary of the U.S. entering World War I, we look back on the history of that conflict, including how the government financed U.S. participation and the consequences of fighting a “war to end all wars.”

How the Fed Helped Pay for World War I by John Paul Koning

Governments can pay their bills in three ways: taxes, debt, and inflation. The public usually recognizes the first two, for they are difficult to hide. But the third tends to go unnoticed by the public because it involves a slow and subtle reduction in the value of money, a policy usually unarticulated and complex in design.

In this article, I will look under the hood of the Federal Reserve during World War I to explain the actual tools and levers used by monetary authorities to reduce the value of the public’s money in order to fund government war spending. This example will help readers better understand the more general idea of an “inflation tax,” and how such a tax might be used in the future to fund the state’s wars.

It is the government’s monopoly over the money supply that allows it to resort to inflation as a form of raising revenue. Kings and queens, by secretly reducing the amount of gold in coins they issued to the public, could use the gold held back to pay for their own pet conquests. Slowly the public would discover that the coins they were using had less gold than the amount indicated on their face. Their value would be bid down, and the coin-holding public would bear the costs in lost purchasing power.

Legal-tender laws adopted by governments prevented the public from exchanging bad coins at less than their face value. A fall in market value, after all, would cut off a significant future revenue source: the government’s ability to issue bad coins at inflated values.

The use of force to subsidize an inferior coin’s value reduced its capacity to provide the holder with certainty, corrupted the informational value of the prices it provided, and diminished the public’s trust in the money. This decline in a monetary system’s efficacy due to bad money and legal-tender laws is always a cost born by the money-using public.

Just as kings debased coins to help pay for their wars, the Federal Reserve used inflation to help pay for US participation in World War I. It did so by creating and issuing dollars in return for government debt. In effect, the Fed’s balance sheet became a repository for war bonds. Furthermore, the Fed brought this debt onto its balance sheet at a higher price than the market would have paid otherwise, a subsidy born by all those who held money as its purchasing power declined.

Before explaining how this process worked, it is necessary to know a few things about the Fed. The institution began operations in 1914 on the “real-bills” principle. Member banks could borrow cash from the Fed, but only by submitting “real bills” as collateral.

These bills were short-term debt instruments that were created by commercial organization to help fund their continuing operations. The bills were in turn backed by business inventories, the “real” in real bills. By discounting or lending cash to banks on real bills, the Fed could increase the money supply.

The original Section 16 of the Federal Reserve Act required that all circulating notes issued by the central bank be backed 100% by real bills. On top of this, an additional 40% gold reserve was to be held by the Fed. In those days, Federal Reserve notes — a liability of the Fed — were convertible into gold, and the 40% gold reserve added additional security. Thus, for each dollar liability it issued, the Fed held 140% assets in its vaults, or one dollar in real bills and 40¢ in gold on the asset side of its balance sheet.

The Fed was also permitted to engage in open-market purchases of government debt and banker’s acceptances. But government debt was not of a commercial nature, and therefore was not considered a real bill. Because the 100% “real”-backing requirement for notes could not be satisfied by Fed holdings of government debt, the Fed could only issue a limited number of notes for government debt before running up against the 100% requirement.

Thus, the real-bills doctrine as set out in the Federal Reserve Act significantly hemmed off the Fed’s balance sheet from serving as a bin for the accumulation of government debt and claims to government debt. To help finance the war, which it had entered into in April 1917, the US government would have to open up the Fed’s balance sheet to the Treasury’s war debt.

Read the rest at the Mises Institute.

View as PDF

Chicago – Taxpayers Untied of America (TUA) and our supporters once again helped defeat home rule referenda in two communities and defeat another property tax increase referendum on the ballot April 4, 2017, now totaling 423 victories on behalf of taxpayers since 1977.

“The voters of both Coal City and Lynwood were wise to resoundingly defeat these home rule referenda,” said Jim Tobin, president of Taxpayers United of America.

“Home rule means granting unlimited taxing authority to local bureaucrats. Why would voters want to cut themselves out of voting on tax increases? Why grant more authority over your hard-earned money?” said Tobin.

“Voters averted more tax hikes from local officials by rejecting to become another home rule unit of government in Illinois.”

Voters defeated Coal City’s home rule referendum by eighty-one percent, 747 to 175.

Lynwood’s home rule referendum was defeated 683 to 221, or by seventy-five percent of voters.

Home rule was last defeated by Lynwood residents and TUA supporters in November 2014, when sixty percent of voters rejected the attempt to have unlimited taxing authority imposed on the community.

TUA and our supporters were successful in defeating Hinsdale Township HSD 86’s property tax increase referenda. The Board of Education wanted to issue $76 million in new bonds, raising property taxes by more than $450 annually, which doesn’t include future property tax hikes to pay $24 million in interest.

Voters rejected the government school property tax hike for Hinsdale by nearly seventy-five percent of voters, or 9,102 to 3,169.

Unfortunately, eighty percent of voters approved Evanston/Skokie CCSD 65’s $450 annual property tax hike. Berwyn South SD 100’s property tax increase barely passed by less than two hundred votes. And Oak Park SD 97 voters passed referenda to raise their property taxes by $13.3 million and issue new bonds totaling $57.5 million. The average Oak Park homeowner will see a spike in their annual property tax bill by more than $700 annually.

Voter turnout was mixed across Illinois, and with the budget stalemate continuing in Springfield, some voters opted for tax hikes in the face sustained campaigns from officials, groups, and other advocates.

But in McHenry Township, TUA can point to other local victories on behalf of taxpayers. The political action arm of TUA, Tax Accountability, endorsed candidates won a number of races. Bob Anderson, Mike Rakestraw, Bill Cunningham, & Stan Wojewski won election as trustees, and Dan Aylward handily won the office of township clerk.

“The budget stalemate in Springfield and the results of these local elections prove how divided Illinoisans are when it comes to taxes and spending,” said Tobin. “More than ever, now is the time to take on the important work of charting new paths for Illinois’ financial future. But our journey won’t be easy unless we consider ways to dump the baggage of the political class which have run the state like the mob for decades.”